The European Union has long had the ambition of rivalling the United States from an economic viewpoint. It actually managed to do so in the late 2000s. In 2008, at current prices, the Eurozone ($14.16 trillion) and United States ($14.77 trillion) had very similar levels of GDP. Students learned about this achievement and politicians basked in its glory, as if it proved the success of the European project.

A good fifteen years later, the situation has completely changed, showing Europe at a disadvantage to the United States in terms of economic performance. The European economy has been stagnant since 2008, whereas the US economy has continued to grow. The gap between the two economic powers’ GDP reached 80% in 2022 ($14.14 trillion for the Eurozone vs $25.44 trillion for the United States). Since the end of 2019, annual growth has averaged 1.9% in the United States but no more than 0.8% in the Eurozone.

Source : OCDE

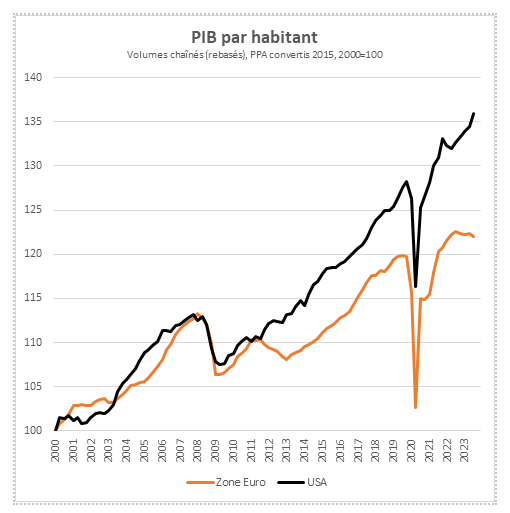

Europe’s uncoupling has been rapid. Looking at changes in GDP per capita each side of the Atlantic since 2000, one thing is clear: whenever there is a crisis, the performance gap between the Eurozone and United States widens. Financial crisis, sovereign debt crisis, health crisis, energy crisis, inflation crisis: shock after shock, the United States has shown greater resilience and stronger powers of recovery than Europe. Last summer, the Wall Street Journal wrote about Europe’s inability to keep pace with America. It drew the following conclusion: “Europeans are becoming poorer.” And this is unlikely to improve in the short term. Whereas the European Commission is forecasting Eurozone growth of 1.2% in 2024 and 1.6% in 2025, US growth is expected to be slightly higher (1.4% in 2024 and 1.8% in 2025). The gap could be even wider if the German economy, in which higher energy costs have hit industry, struggles to bounce back. In the United States where energy is abundant and cheap, the energy crisis facing Europe is having the opposite effect: it has generated competitivity gains and even boosted foreign trade, as the United States became the world’s biggest exporter of liquefied natural gas in 2023.

However, these circumstantial elements cannot explain the uncoupling on their own. We should also mention that the European Union and United States are not tackling the crises with the same instruments. Limited to fiscal orthodoxy by its very nature (the Eurozone is not a fiscal union and is therefore exposed to financial markets’ reactions), the European Union does not have the same liberty to issue debt as the United States. Whereas the US annual deficit will be more than 7% in the coming years after peaking at 14.7% in 2020, that of the Eurozone will probably remain below 3% in 2024 and 2025. West of the Atlantic, this deficit is financing highly ambitious recovery plans, such as the famous (and badly misnamed) Inflation Reduction Act, under which $400 billion will be spent on the energy transition. Such budgetary insouciance is possible because the dollar remains the world’s number one reserve currency. Maybe we’ll have to start worrying about the United States’ debt levels one day. But in the meantime, these political choices have given the US economy the oxygen so cruelly lacking in Europe.

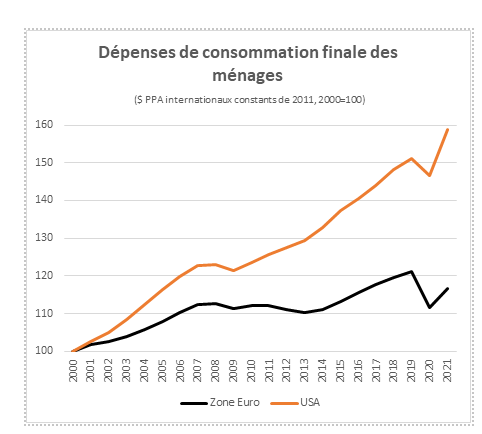

This strategic interventionism has been particularly decisive in two ways. Firstly, by stimulating consumer spending, which is much more buoyant than in Europe. In times of crisis, US state support has generously underpinned demand – the main driver of US growth. During the health crisis, it enabled Americans to build up savings, massive amounts of which have since been spent.

Source : Banque Mondiale

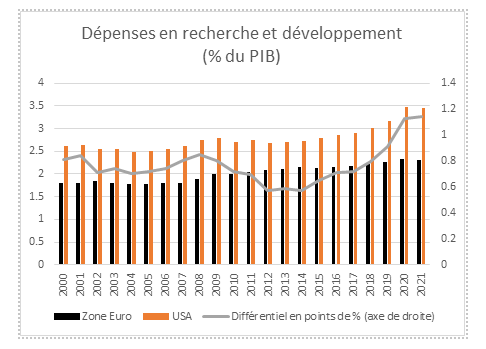

Secondly, by catalysing innovation. Through subsidies and tax cuts, the United States has encouraged R&D projects, especially in IT/communications and the energy transition. The United States, which already had a big advantage in this area, has extended its lead over Europe in recent years, as the chart below shows. In 2021, R&D expenditure accounted for 1.14 percentage point of GDP more in the United States than it did in the Eurozone.

Source : Banque Mondiale

The US economy does not owe the superiority in innovation solely to government stimulus. It is also boosted by the performance of its national champions. Gafam (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft) and Natu (Netflix, Airbnb, Tesla and Uber) have invested billions of dollars in research and development over recent years, to consolidate and increase their domination of their respective markets on a winner-take-all basis. The cumulative value of the Gafam is now approaching $10 trillion. This figure may seem artificial, but reflects the companies’ extraordinary development capacity, especially in highly strategic fields such as artificial intelligence. With its immense domestic market providing a tremendous incubator for high-potential companies, the United States has succeeded where Europe has failed. In the last 20 years, how many global companies have truly emerged in Europe?

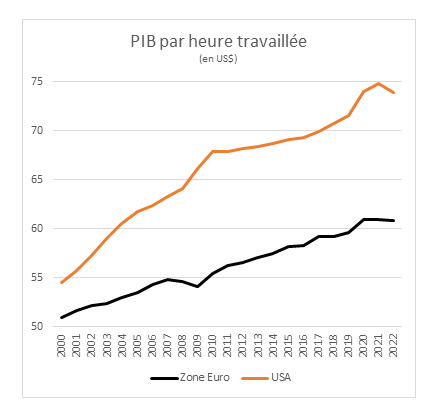

Unsurprisingly – and this is another explanation for Europe’s uncoupling – in an economy where innovation occupies a bigger space, the United States has also seen its labour productivity (already structurally higher than in Europe) rise much faster than Europe’s in recent years.

Source : OCDE

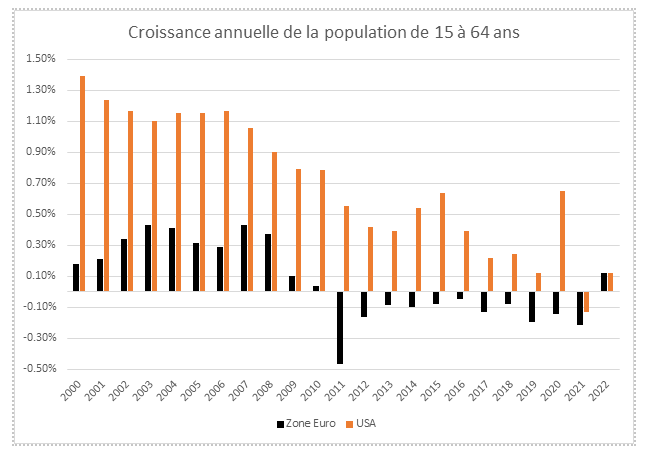

This productivity gap is all the more worrying for the long term if we look at the two economies’ demographics. Historically more populated, Europe has seen its demographic advantage fade over the years. Due to ageing, negative growth in the working-age population (-0.2% per annum in the Eurozone) is the main concern, as it is in the United States where there is stagnation after years of strong growth. Until now, Europe has managed to offset this loss by calling on other sources of labour (reducing unemployment). However, in the medium- and long-term this will not be enough.

Source : Banque Mondiale

Unless there are big labour productivity gains in Europe, the economic gap could widen further due to a lack of available workers. The United States is facing the same problem of an ageing population but seems culturally more inclined to rely on immigration. Migration policies are still very contentious in Europe and it will be hard to reach an democratic consensus on the matter.

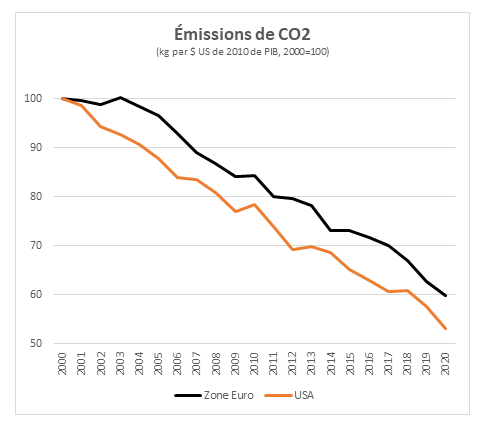

Some may say that Europe’s demographic weakening and economic slowdown is good news for our planet. That it will help us to achieve our climate goals. But growth is actually the planet’s best ally. We need this growth to invest in the new technologies that will enable future generations to live better than previous ones, while respecting the environment. The United States has demonstrated this. Despite firmer growth, the United States has managed to reduce the carbon intensity of value added (which nonetheless remains much higher than in Europe) to a greater extent than Europe in the last 20 years.

Source : Banque Mondiale

However, US growth is not perfect. It has not helped to eradicate the significant imbalances in the United States’ social model. The Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, is still much higher in the United States (0.395% in 2022) than in every European country (0.284% in Luxembourg, for example). The same can be said about poverty (percentage of individuals living on half of the national median income), which was 10.2% for the Eurozone in 2022 but 18% for the United States. This social disparity can also be seen in life expectancy, which is increasing more quickly in the Eurozone than in the United States. In 2000, life expectancy was 1.63 years higher in Europe than the United States. It was 5.37 years higher in 2021.

Europe’s social model remains its primary asset. And it’s not the only one. Europe’s impoverishment and relegation to being a secondary economic power is not fatal. With its productive fabric, ability to produce knowledge, demonstrably strong currency, and progress in the environmental transition, Europe still has some cards up its sleeve. It just needs to play them right. Rather than increase the red tape that puts businesses at a disadvantage to their international competitors, European institutions will need to focus their efforts on drawing up innovative policies to encourage R&D, stimulate productivity, create European champions, increase energy and digital sovereignty, kick-start industry, and help overcome demographic challenges. These are decisive issues not just for Europe but for our country: Luxembourg will not be strong unless Europe is strong.

These realisations make European competitiveness, and the economy in general, central to debate ahead of European elections on 9 June. As Bill Clinton’s advisor, James Carville, said: “It’s the economy, stupid!”.