As one of the most open economies in the world, the question of free trade is of tremendous importance for Luxembourg. Free trade is not only about a sound economic situation, but also the well-being of citizens, especially the less well-off, and the environment. Is free trade inherently bad for these three pillars of sustainable development, or are sustainable development and free trade actually two sides of the same coin?

I would argue that the two can go hand in hand, provided that a few preconditions are met. Accordingly, there are three key frequent misconceptions to consider from an economic, social, and environmental perspective when looking at the question of free trade and sustainable development.

Economics: Deindustrialisation?

The first misconception is that free trade would deindustrialise our respective countries, dismantle factories, weaken craftsmanship, and therefore subsequently eradicate all pertinent skills and savoir faire.

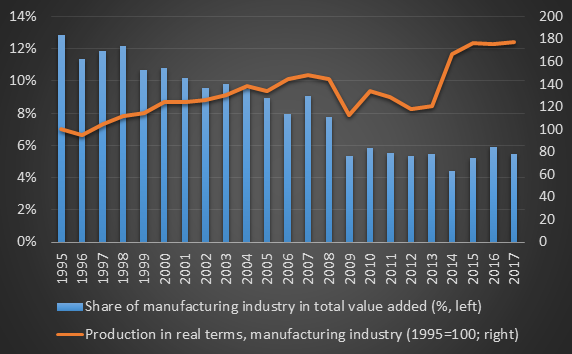

It is true that we must be vigilant to ensure an effective level playing field in this respect and provide a good business environment to industry. However, we should not exaggerate the real extent of deindustrialisation in the advanced economies. Considering Luxembourg’s situation, we know that the manufacturing industry has declined continuously since 1995 as a percentage of total value added (see Chart 1). Some might say that this is a striking confirmation of a dramatic decline in industry that reflects this ‘terrible globalisation’ and the correlative shift of activities to Asian and other developing countries.

But that impression and the underlying indicators are totally misleading. In absolute terms, our manufacturing industry has continued growing, as indicated by the orange line in Chart 1, which shows the evolution of total manufacturing production in constant prices. The trend is positive, in spite of the adverse impact of the economic and financial crisis.

Within a global value chain, namely a combination of products and services reflecting the various comparative advantages of nations worldwide, Luxembourg increasingly specialises in high value services and products, which are extremely positive for Luxembourg’s economy. At the same time, growth in these sectors accentuates perceptions of industrial decline. As shown in Chart 1, industry is indeed still alive in Luxembourg and elsewhere in Europe. Yet, from a statistical point of view, the line between industry and services is not always evident. Many industries of the future are indeed measured as services, and this further magnifies what I would qualify as the ‘disappearing industry’ fallacy.

The situation is not as dramatic as is commonly believed and with a business friendly environment, more insistence on human capital, research, development, and innovation, we can sort our way out in industry and elsewhere. In fact, a good place to start would be by further fostering digitalisation and dynamic start-ups.

All in all, we stand to gain from free trade at the aggregated level. The IMF has recently identified at least four channels through which open markets could boost the economy, namely: (i) via the reallocation of resources to the most productive sectors; (ii) via lower tariff uncertainty, essential for the decision of firms to enter the export market; (iii) via offering a wider range of goods and services at lower prices for households or firms; and (iv) via the early adoption of advanced technologies, which is stimulated in a free trade environment. For instance, in a study on Mercosur mentioned by the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO[1], a reduction in Brazil’s tariffs by only 1% tends to stimulate firms’ technology spending by between 1% and 1.5% in Argentina.

A safe contention is that free trade, apart from exceptional circumstances, enhances economic growth. But this is an aggregated effect. Do the economic gains of open markets trickle down to all of us, irrespective of our incomes, professions, sectors, or where we live?

Is free trade ‘social’?

This is the central question of the second misconception around free trade and sustainable development, namely the social consequences of free trade. It is frequently argued that free trade would make winners but also losers. It would increase inequalities and tend to undermine social cohesion.

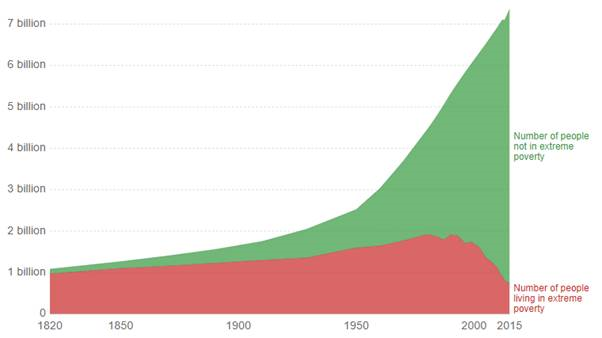

Here, I think, we should make a distinction. On a global level, the process of globalisation observed over the last decades went hand in hand with a spectacular decrease in poverty. As clearly illustrated in Chart 2, the number of persons in extreme poverty fell considerably in the last 25 years, as extreme poverty (namely people living on less than $1.9 a day) decreased from 1.9 billion in 1990 to 735,000 – minus 60%. Other factors could have played a role, but at least the trend is incredibly favourable.

Having said that, we must, however, also consider the social situation within advanced economies and wealthy countries.

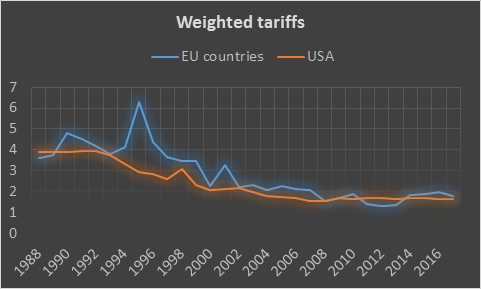

The impact of trade on inequalities in advanced economies should not be exaggerated. The mere observation of macro data is far from compelling, as shown in Chart 4, which compares average tariffs to inequality measures. Tariffs have fallen considerably since 1980, both in advanced and developing economies. At the same time, relative inequality measures – here the share of total pre-tax income accounted for by the top 10% – evolved in a rather different way.

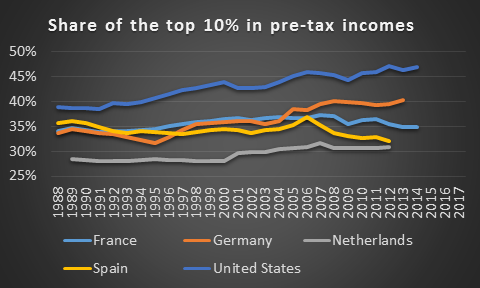

The data for the United States in Chart 3 suggests a link between more open markets and rising inequalities. But the situation is much more complex in the EU, where the evolution of average tariffs was of course different from country to country. In Germany, the relative inequality indicator increased in a significant way (reflecting a higher concentration of incomes), which seems similar to the United States – albeit from a different starting position. In France, however, the indicator stagnated from about 2000 onwards, in Spain it declined, and in the Netherlands it increased slightly, but from a comparatively low level. Thus, there are strikingly different experiences, in terms of relative inequalities, in the same trade environment. This leads me to consider that issues other than just free trade are at stake, that free trade is no more than a convenient scapegoat.

The case against free trade would be even less convincing should absolute indicators based on material deprivation be used instead of relative poverty indicators. Overall, free trade tends to make the cake bigger, which is not at all demonstrated in these relative indicators, by definition.

It is frequently quite difficult to decipher macro indicators but several well targeted micro studies have been undertaken in parallel, and generally show that free trade tends to enlarge the access of consumers to less pricey goods and services, which means increasing purchasing power for the people most in need. The less well-off are indeed inclined to spend a larger proportion of their income on tradeable goods.

The favourable impact of free trade on the GDP could also stimulate employment, including for low-wage earners.

Nonetheless, we must be extremely vigilant in order to ensure that the economic benefits of free trade are well distributed in advanced economies, via more targeted social protection expenditures, for instance. Another less intuitive but potentially powerful tool against poverty could proceed via micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSME), as they tend to provide good quality jobs in an inclusive way. But, according to the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO[2], direct exports by MSMEs amount to only 7.6% of total MSME sales in the manufacturing sector, compared to 14.1% for large manufacturing enterprises. We should find better ways to integrate these companies in international trade, on economic but also on social grounds.

Furthermore, if we look at the current (very uncertain) situation in the UK, according to the Bank of England[3], a hard, disorderly Brexit would increase the unemployment rate in the UK from the current 4% to about 7% in 2020-2021. Is it really social?

The environment

Finally, the third commonly held misconception about open markets and free trade, the evil ‘Homo Economicus’ at its worst, is that it has no consideration at all for environmental issues. Open markets inevitably have a negative impact on the environment, leading to more pollution, CO2, etc.

Yes, we must address these issues and the status quo is no longer an option. But, once more, we should not overreact, we should instead stimulate – via taxation or other tools – more conscientious behaviour by firms and households to promote a circular economy and to modernise energy production and consumption. But we should certainly not push the market economy overboard: reform, not revolution.

We have to keep in mind that free trade agreements remain the most efficient tools to promote an ambitious level playing field in this regard. Let’s be ambitious!

Past experiences of planned economies in Eastern and Central Europe show that free trade is not the problem. The solutions should be investigated in conjunction with, not against, free trade. The market economy is geared towards efficiency gains and innovation in green technologies. Market devices like flexible emission trading schemes could help. This is qualitative growth, which means less resources for the same unit of GDP. There are no such incentives in heavily regulated or planned economies. The former USSR’s share of CO2 emissions increased from 12% to 16% of total global emissions from 1950 to 1991[1]. The fates of Lake Baikal and the Caspian Sea indicate where these statistics lead.

We should combine the three dimensions – economic, social and environmental – in a global and compelling way. Economic progress contributes to social cohesion, which ensures political stability. Stability is in turn fertile ground for intelligent and dispassionate discussions about free trade and environmental issues.

Chart 1: Manufacturing industry – Share in value added and real production

Chart 2: World population living in extreme poverty, 1820-2015 (number of people)

Extreme poverty is defined as living on less than Intl.$1.90 (international dollar) per day. International dollars are adjusted for price differences between countries and for inflation.

Chart 3: Income distribution within advanced nations(as %)

Chart 4: World Trade Organization – Weighted custom duties on all products (as %)

[1] See Reinvigorating trade and inclusive growth, IMF, World Bank and WTO, September 2018, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2018/09/28/093018-reinvigorating-trade-and-inclusive-growth.

[2] See Reinvigorating trade and inclusive growth, op. cit.

[3] See EU withdrawal scenarios and monetary and financial stability – A response to the House of Commons Treasury Committee, Bank of England, November 2018, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/report/2018/eu-withdrawal-scenarios-and-monetary-and-financial-stability.pdf.

[1]Marland G., Boden T.A., Andres R. J. 2000, Global, Regional, and National CO2 Emissions. In Trends: A Compendium of Data on Global Change. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tenn., U.S.A.